The klaxist vanguard

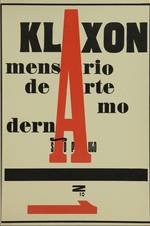

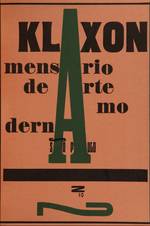

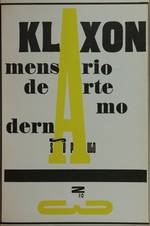

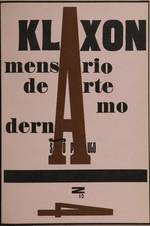

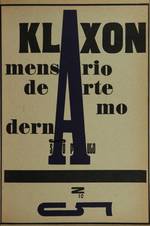

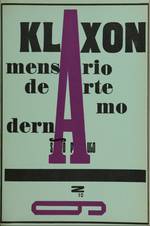

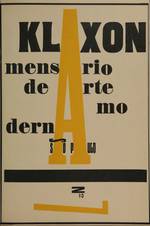

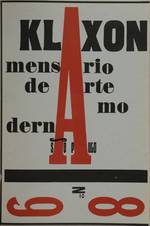

Klaxon is considered the first Brazilian modernist magazine. A later product of the 1922 Semana de Arte Moderna, it was launched in May, two months after the event ended. According to Guilherme de Almeida, its publication was not previously planned, and was rather a necessary consequence to ensure that the spirit of the Semana was not lost1. The magazine was produced by the group of intellectuals who spearheaded the modern art movement in Brazil, acting as an instrument for the ideas and creations that had been presented to the public at the sessions of the municipal theatre in São Paulo. It was the medium through which the group expanded its ideas, discussed and criticized the artistic production of its time, and published fragments of its literary production.

The inaugural issue includes a manifesto that presents the publication’s intentions, divided into four parts: “Significação”, “Estética”, “Cartaz”, and “Problema”. “Significação” recalls the beginning of the modernist struggle in 1921, waged in the Jornal do Commercio and the Correio Paulistano, as well as in the Semana de Arte Moderna itself, and it is made clear that Klaxon is meant to reflect, clarify, and build on the mistakes previously committed. An argument is made that Brazil should try to understand the publication, while outlining an avant-garde position.

“Estética” asserts the magazine’s current, internationalist character, with a transforming and even deforming vision of nature. It positions itself as klaxist rather than futurist, suggesting a desire for independence. On this subject, while taking a stand in favour of new languages and technologies, a comparison is made between Pearl White, a film artist, and Sarah Bernhardt, a representative of nineteenth-century theatre. Bernhardt was associated with tragedy, with sentimental and technical romanticism, and should be replaced by White with reasoning, education, sport, speed, joy, life, since at the time cinema was held as the most representative artistic creation.

“Cartaz” approaches the historical period as the time of technique and compares the magazine’s contributors to engineers, free to use whatever materials they wanted to experiment with and write.

Finally, “Problema” proclaims romanticism and symbolism as movements to be supplanted through joyful construction, since the era of laughter, of sincerity, of construction, in short, “the era of Klaxon” had arrived.

Despite the manifesto’s proposals for reflections, the periodical’s actions were combative and critical, with a view to validate the expressions of modern art at the expense of movements that were considered outdated. Fictional productions, literary criticism, and articles extolled new media and technologies, such as cinema and the airplane, and spurned Parnassianism and romanticism, referring to their authors as passadistas.

There is no mention of the team who oversaw the publication. However, according to records by Joaquim Inojosa, Rubens Borba de Moraes was the person in charge of tasks related to subscriptions, advertisements, and contributions2. This effort is explained by the fact that Borba considered it strategic for the group to have at its disposal a magazine which allowed it to say what it wanted, disseminate experimental works, and engage in polemics with those who would not risk joining the new ideas3. While the latter was crucial in articulating the practical aspects of the publication, Mário de Andrade was the protagonist in terms of contributions, notes, criticisms, and reports.

Klaxon's collaborators were called klaxists in the magazine, a designation that signalled their inclusion in the family of modernism and internationalism, as intended by the publication. The search for this positioning is manifested graphically, through the experimental content, the use of different languages, the relationship with foreign magazines. In any case, Klaxon does not align itself with any artistic vanguard, but clearly states its opposition to Marinetti's Futurism, rebutting press criticism that associated Klaxon's proposal with the Italian movement.

Its target audience was an elite interested in avant-garde art, so much so that friendly relationships with some foreign periodicals, always endorsed in the “Livros e revistas” section, such as the Belgian Lumière, the French La Nouvelle Revue Française, the British Fanfare, among others, were cultivated. Notably, an exchange of collaborations took place between intellectuals from these magazines and the klaxists.

The publication was financed by the contributors themselves. They failed to sell advertising content, with only two ads being printed in the first two issues. Furthermore, the subscription system was not successful, as it only attracted one subscriber who, despite having paid the annual rate, returned the inaugural instalment, on the grounds of having no interest in receiving further issues, deeming the magazine’s content incomprehensible. Despite having forfeited the amount paid, Guilherme de Almeida recalls that the subscriber's request was not granted, and that he eventually received all the issues published4.

The elements that characterised Klaxon's publication, such as contributors, content, graphical layout, and critical positioning, show that the magazine intended to renovate the artistic formulations of its time and constituted an appropriate medium to freely disseminate the modernist group’s production.

Letícia Pedruzzi Fonseca

-

Guilherme de Almeida, Folha de São Paulo, 1968. Apud Plínio Doyle, História de revistas e jornais literários, vol. 1, Rio de Janeiro, Ministério da Educação e Cultura, Fundação Casa de Rui Barbosa, 1976.↩︎

-

Plínio Doyle, História de revistas e jornais literários, vol. 1, Rio de Janeiro, Ministério da Educação e Cultura, Fundação Casa de Rui Barbosa, 1976.↩︎

-

Cecilia de Lara, Klaxon & Terra Roxa e outras terras: dois periódicos modernistas de São Paulo, São Paulo, IEB/USP, 1972.↩︎

-

Guilherme de Almeida, Folha de São Paulo, 1968. Apud Plínio Doyle, História de revistas e jornais literários, vol. 1, Rio de Janeiro, Ministério da Educação e Cultura, Fundação Casa de Rui Barbosa, 1976.↩︎